Definition

The critical engine twin engine aircraft concept refers to the engine whose failure produces the most adverse aerodynamic and handling effects on a multi-engine airplane. When this engine fails, the remaining engine generates asymmetric thrust that challenges stability, control, and pilot workload. Understanding which engine is critical — and why — is fundamental for flight safety, training, and performance management in all multi-engine aircraft.

In most conventional twin-engine airplanes with propellers rotating clockwise when viewed from the cockpit, the left engine is considered critical. This is due to how aerodynamic forces combine during asymmetric thrust situations, creating stronger yawing and rolling tendencies that the pilot must counteract.

Understanding Thrust Asymmetry and Aerodynamic Effects

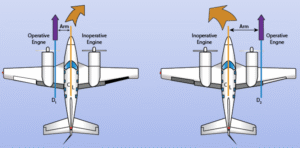

When one engine in a twin engine aircraft becomes inoperative, a thrust imbalance occurs between the operative and inoperative sides. This imbalance results in asymmetric yaw and roll moments, which can cause significant control challenges. The pilot must apply coordinated rudder and aileron input to maintain straight flight.

This thrust asymmetry also influences climb performance and minimum controllable airspeed (V<sub>MC</sub>). The aircraft will always perform worse when the critical engine fails because the remaining operating engine produces its thrust further from the aircraft’s centerline, creating more yawing force.

Asymmetrical Yaw and P-Factor Influence

When the critical engine twin engine aircraft scenario occurs — that is, the critical engine fails — the pilot faces immediate yawing toward the dead engine. This happens because of the P-factor, or asymmetric blade effect: in a clockwise-rotating propeller, the descending blade on the right produces more thrust than the ascending blade on the left.

Thus, when the left engine fails, the thrust from the right engine acts further away from the center of gravity, producing greater yaw and roll. This aerodynamic condition demands higher rudder input and precise control to prevent loss of directional stability. The failure of the left engine is, therefore, less desirable — it is the critical engine failure case.

Aircraft with counter-rotating propellers, such as the Beechcraft Duchess, are designed to eliminate this effect, as both engines turn in opposite directions, balancing aerodynamic forces and removing the concept of a single critical engine.

Accelerated Slipstream and Lift Distribution

Another aerodynamic factor contributing to critical engine twin engine aircraft behavior is accelerated slipstream. The propeller wash over the wing increases the airflow speed and lift behind each engine. When the critical engine fails, the wing on that side loses this additional lift, creating both a rolling and yawing moment toward the inoperative engine.

This asymmetry not only affects lift distribution but also drag, resulting in a reduced climb rate and an increased stall risk on the dead side. The pilot must counteract this with rudder pressure and bank angle toward the operative engine to maintain control and climb capability.

Non-Aerodynamic Criticality and System Dependencies

In some aircraft, the concept of the critical engine twin engine aircraft extends beyond aerodynamics. One engine may power vital systems such as hydraulics, electrics, or pneumatics. If that engine fails, critical flight instruments, gear retraction, or deicing systems may also fail.

In this case, the affected engine is operationally critical, even if aerodynamically it is not. Examples include older light twins and certain turboprops where accessory drives are mounted on one engine only.

Counter-Rotating Propellers and Modern Design Solutions

Modern aircraft designers have worked extensively to reduce the aerodynamic challenges associated with critical engine twin engine aircraft performance. One of the most successful engineering advancements is the use of counter-rotating propellers, where each propeller spins in the opposite direction. This configuration eliminates the asymmetric thrust that typically makes one engine critical. Aircraft such as the Piper Seminole and Beechcraft Duchess are prime examples of this approach, featuring propellers that rotate inward toward the fuselage. By aligning the thrust vectors closer to the aircraft’s centerline, these designs ensure balanced aerodynamic forces, allowing smoother handling and improved safety in the event of an engine failure.

Counter-rotating systems not only reduce yaw but also enhance stability and control during takeoff and climb — phases where engine-out performance is most critical. Pilots transitioning from conventional twin engine aircraft to counter-rotating models often note the difference in handling precision and reduced rudder input requirement. Although these designs eliminate the traditional “critical engine,” they still require precise technique, as asymmetric drag and rolling tendencies can still appear under partial power or propeller feathering conditions. Thus, modern engineering reduces but never completely removes the need for pilot awareness of critical engine dynamics.

Critical Engine Twin Engine Aircraft and Training Implications

Understanding critical engine twin engine aircraft behavior is fundamental in multi-engine training programs. Student pilots learn to recognize engine-out symptoms and perform the Identify–Verify–Feather sequence instinctively. The concept emphasizes directional control through coordinated rudder and aileron inputs, proper bank angle, and maintaining best single-engine climb speed (V<sub>YSE</sub>). During simulator and in-air lessons, instructors stress the difference between engine failures on the critical and non-critical sides, ensuring pilots grasp how asymmetrical thrust and yaw affect performance and controllability.

Training also includes V<sub>MC</sub> demonstrations, where instructors simulate failures near the minimum controllable airspeed to teach students the limits of aircraft stability. These exercises reinforce awareness of critical engine principles and show how improper control inputs can cause VMC rollovers. For professional aviators, recurrent training keeps engine-out decision-making sharp — especially important for operators of twin engine aircraft in commercial and charter environments. Proper training transforms theoretical knowledge of the critical engine into real-world competency, directly enhancing flight safety.

Turbojet and Turbofan Aircraft — Why No Critical Engine Exists

In jet propulsion systems, the traditional critical engine twin engine aircraft concept largely disappears because of engine placement and thrust symmetry. Turbojet and turbofan aircraft typically mount engines close to the fuselage or symmetrically under each wing, meaning the yawing moment generated by a single engine failure is much smaller. These aircraft rely on yaw-dampers, automated thrust management, and advanced flight control systems to maintain stability after a power loss. As a result, the “critical engine” designation, so relevant for propeller-driven aircraft, holds little practical importance in jet operations.

Still, twin engine jet aircraft are not immune to asymmetric thrust challenges. High-bypass turbofan designs can produce substantial lateral forces, especially at low speeds or during takeoff. Pilots receive specific training to counteract yaw and roll using rudder and coordinated thrust management, applying the same aerodynamic reasoning behind the critical engine theory. Therefore, while modern jets no longer have a defined critical engine, understanding asymmetric flight dynamics remains essential for safe multi-engine operations.

Conclusion

The critical engine twin engine aircraft principle remains one of the cornerstones of multi-engine flight theory. It combines aerodynamics, human factors, and system design into a single safety concept that every pilot must understand. Knowing which engine is critical, how to handle asymmetric thrust, and how to react instinctively under pressure is what separates competent multi-engine pilots from unsafe ones.

From propeller aerodynamics to system dependencies, the study of the critical engine reflects aviation’s focus on balancing engineering and human performance. As technology advances, counter-rotating designs and improved training continue to make multi-engine flight safer and more predictable.

For an in-depth story about twin-engine operations in extreme environments, explore

👉 Twin Otter Aircraft Arctic Stories